Last week those of us in the Carolinas got a reminder of how we’re all connected to everything, including things we’d maybe rather not be, like hurricanes. Nature, as it turns out, is indifferent to those kinds of petty desires.

The question of how we are all interconnected, whether we like it or not, and what that means for individual freedoms, is central to The Dreaming Land trilogy, the first book of which is set for official launch next week. I had originally planned it for today, the equinox, but the hurricane and my own general tardiness derailed my plans. So September 29th it is. Which happens to be the day of the hobbits’ arrival in Bree in The Fellowship of the Ring. I didn’t originally plan it that way, but now it seems appropriate to release each book in The Dreaming Land trilogy on some significant LOTR day, given how central LOTR is to my story.

Although the official launch date and related free promos aren’t until next week, TDLI is already live on Amazon for ARC readers to leave reviews if they feel inclined. It will be much appreciated if you do!

Like for many lovers of fantasy, The Lord of the Rings made a huge impression on me, and I’ve worked it into my books in many ways. Perhaps one of my favorite scenes is the ride through the Old Forest near the beginning of The Fellowship of the Ring, when the forest keeps driving the hobbits in the wrong direction until they end up lost. I worked a similar scene into The Midnight Land I, when snow drifts keep driving the party in circles until they end up facing the wrong way, even as their compass fails and the snow is coming down so thickly they can’t guide themselves by the sun or the stars.

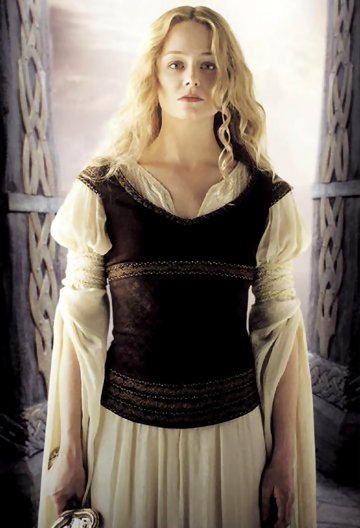

But as a horse-loving girl with strong feminist inclinations, it was the character of Eowyn who most fascinated me. Fascinated but horrified. Although the movie version of Eowyn is presented as your typical modern ass-kicking “strong” heroine, and is probably most associated with her “I am no man” speech as she kills the Witch-King of Angmar:

the book version of Eowyn has a much sadder story.

When Rohan sets off to come to Gondor’s aid in The Return of the King, Eowyn asks Aragorn to take her with him when he goes on what she thinks is a suicide mission to Dunharrow:

“Your duty is with your people,” he answered.

“Too often have I heard of duty,” she cried. “But am I not of the House of Eorl, a shieldmaiden and not a dry-nurse? I have waited on faltering feet long enough. Since they falter no longer, it seems, may I not now spend my life as I will?”

“Few may do that with honor,” he answered. “But as for you, lady: did you not accept the charge to govern the people until their lord’s return? If you had not been chosen, then some marshal or captain would have been set in the same place, and he could not ride away from this charge, were he weary of it.”

“Shall I always be chosen?” she said bitterly. “Shall I always be left behind when the Riders depart, to mind the house while they win renown, and find food and beds when they return?”

“A time may come soon,” said he, “when none will return. Then there will be need of valour without renown, for none shall remember the deeds that are done in the last defense of your homes. Yet the deeds will not be less valiant because they are unpraised.”

And she answered: “All your words are but to say: you are a woman, and your part is in the house. But when the men have died in battle and honour, you have leave to be burned in the house, for the men will need it no more. But I am of the House of Eorl and not a serving-woman. I can ride and wield a blade, and I do not fear either pain or death.”

“What do you fear, lady?” he asked.

“A cage,” she said. “To stay behind bars, until use and old age accept them, and all chance of doing great deeds is gone beyond recall or desire.”

The Return of the King, 67-8, 1965.

Eowyn does disguise herself as a man and ride into battle with Rohan, killing the Witch-King of Angmar when no one else can. Her deed, though, is greeted with at least as much horror as it is praise. And her “reward” for it is to be locked in the Houses of Healing while most of the men go off to fight, and lectured by Faramir on her selfishness and callowness. The end result is that she is married, ostensibly voluntarily, to Faramir. And although she is presented as being happy about it, what she says she fears the most is the thing that, on a certain level, comes to pass: she becomes chattel to be bartered in a marriage alliance, and she accepts it.

Eowyn has little to celebrate, even after she is given a token crumb of respect and recognition

Tolkien shows an acute understanding of the central injustice of women’s lives in Eowyn’s speech at the beginning of The Return of the King. As he clearly understands, and has Eowyn say, women’s work is less valued because it is done by women. And it doesn’t matter what that work is, as we see in our own society with the “pink collar ghetto” of, for example, much of higher education, which has dropped in value as a career choice even while IT has become prestigious and high-earning, as–oh funny thing!–IT has become a largely male profession, and education, especially in the humanities, an increasingly female profession. The call to enlist girls to IT and STEM fields, if successful, could very well have the effect of driving those wages back down, rather than lifting women up, if the underlying sexism behind our valuation of professions is not addressed.

Returning to The Lord of the Rings, women may be able to do great deeds in battle, but it will either go unheralded, or they will be declared selfish for wanting to take what should rightfully belong to men. At the same time, society is dependent on their labor, so they are considered doubly selfish if they attempt to break out of the oppressive roles assigned to them, both for stealing from men and for refusing to care for those who are, in fact, dependent on them.

But Tolkien fails to offer any solution, probably because he couldn’t imagine what that solution would be. After all, as Aragorn says, if Eowyn rides into battle, then someone else will have to stay behind to do the duty that had been laid upon her. Aragon, and Tolkien, clearly think it is better for Eowyn to suffer and be exploited than for a man to do so in her place; that things could be organized in such a way that no one would have to suffer and be exploited is not offered as an option.

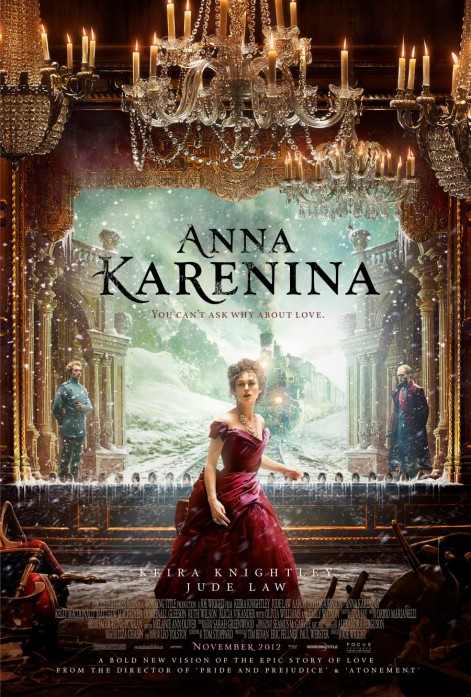

Anna Karenina may seem very different from The Lord of the Rings, but its central problem is sadly similar. Although it is often billed as a love story,

This poster for the 2012 English-language screen adaptation places Anna in the center of a love triangle

there is in fact precious little love in it. Anna and her husband certainly don’t love each other, and the relationship between Anna and Vronsky could best be described as selfishness on his side, and desperation on hers. As she says, she is “starving” for romantic and erotic love, and throws herself at Vronsky like a famine victim at a feast. And while Viktor Shklovsky might argue in Energy of Delusion: A Book on Plot that we don’t judge a starving person for eating, in fact we do. Starving people are not supposed to eat if it might in some way take food away from non-starving people, or make non-starving people feel like they shouldn’t eat so much.

Chekhov said something along the lines that in Anna Karenina Tolstoy had set out the question, without providing an answer, but he had set out the question so well that there was no need, artistically speaking, to answer it. Many women might beg to differ. As with Tolkien, Tolstoy was acutely aware of the injustice facing women, who could not have independence, respect, social status, children, and romantic/erotic love, or at least not generally all at once. Because women were (and are) the primary caretakers of children, they could not abdicate their socially designated roles without leaving society’s most vulnerable members uncared for. The trap for women was not just that they themselves would be punished for transgressing the boundaries set for them, but that others, normally others whom they loved deeply and who depended wholly on them, would be too. Anna’s affair with Vronsky is a tragedy not just for her but for her children, and it is Anna’s abandonment of her children, and her use of birth control, that is seen by Dolly and Tolstoy as the most monstrous of her acts. At the same time, Dolly is also trapped. She accepts her cage, just as Eowyn fears she will accept her own cage (and eventually does), but is not particularly happy about it.

Neither Tolkien nor Tolstoy can imagine a way out for their heroines. One of their stumbling-blocks is the fact that, just as they say, no one is truly free from responsibilities and duties, men as well as women. But at the same time, women in their stories, and in real life, are laden down especially heavily with responsibilities, and are not given the same power and respect in exchange for them than men are. Being a war-leader or a king in The Lord of the Rings, or a rich male aristocrat in Anna Karenina, is not the same as being free, but it is a position of power and renown, and gives much more freedom and respect than being a woman, regardless of position and social class. Both Tolkien and Tolstoy are able to put their finger on at least some of the problem, but are unable to solve it.

I certainly can’t claim that either I or my heroines have solved it, but it is something that Valya from The Dreaming Land grapples with throughout the series. I envisioned her in part as a more empowered version of Eowyn in a female-led society, just as some of my male characters are gender-reversed versions of Anna Karenina, but the same fundamental problems are still there: no one is 100% free, so any struggle for absolute freedom will always be doomed to failure.

So what do you do? Is freedom the right word at all, or have we been framing the question wrong all these years? Should we be searching for something other than freedom as we currently understand it (and is our understanding of freedom in some way fundamentally masculine?), and how can we live in an interdependent environment without being oppressed and exploited, or oppressing and exploiting others? Valya spends a lot of time thinking about it, just as Tolkien and Tolstoy did, but unlike them, she tries to come up with real, fresh answers, and her answers differ from what theirs are. But what would actually work in the world in which we live, instead of a fantasy world, is another question entirely.

Some links:

The Dreaming Land I, if you feel moved to leave a review, or want to read it (free on KU!) ahead of its official release date.

The Midnight Land I, in which the matriarchal land of Zem’ is introduced.

The Midnight Land II, in which among other things a male character undergoes many of the same problems as Anna.

AND–lads, lads, lads!–I have a new story about a completely NEW world in the upcoming anthology The Magical Book of Wands, which you can pre-order for the low low price of $3.99 here.

This is a tremendous essay, Elena!

It’s interesting how authors such as Tolstoy and Tolkien seemingly have some sense of feminist issues, yet their understanding is horribly limited. In the case of “The Lord of the Rings,” for instance, the great scene you cite and discuss is a very small part of a trilogy that — while fantastic — is 99.9% male-oriented. In more modern lit, the amazing writer Cormac McCarthy is also guilty of an almost total focus on men and the male perspective.

Last but not least, congratulations on your new book!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks, and yes, both Tolstoy and, to a lesser extent, Tolkien, seemed very sympathetic to some aspects of the female experience and could accurately diagnosis at least some of the problem—but they just couldn’t seem to come up with a solution, maybe because the solution would involve a more equal distribution of housework and childcare. I thought Aragorn’s comment about how if Éowyn didn’t stay behind, then some man would have to, to be very telling. He recognized the work as essential but also considered it to be beneath men to do it, so clearly women should do it and stop whining about it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So much male self-interest is part of not understanding!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Or maybe only understanding the problem but not being able to see a solution.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s stating it better, Elena! Not being able to see a solution, and perhaps not wanting to see a solution.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating article, Elena. So interesting that you compare the role of the female in these two great novels. I read TLOTR years ago, too long ago to remember exactly how Éowyn was portrayed. As for Anna, yes, Tolstoy starts out with sympathy towards her situation, and makes it clear that her brother Oblonsky gets away with his affairs, and that it’s not fair that Anna doesn’t. And so he raised a social issue. But he did kill her, as he killed Hélène in War and Peace. Clearly he saw no acceptable solution for them. And I really do think that his private views on women were much more old fashioned.

Great news about your new book 😊

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks! And yes, Tolstoy has always struck me as torn between his native sympathy for others, including women, and his native selfishness, to be perfectly honest!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, he was extremely selfish 😄

LikeLiked by 1 person