When I conceived of Valya, the heroine of The Dreaming Land, I knew I wanted her to be…bad. You know, like a bad girl. And really bad, not just fake bad. But I also wanted her to be sympathetic, which created a challenge.

You see, while there are plenty of literary tropes and lots of good will for bad boys, it’s much harder to create a bad girl that readers are going to sympathize with. Boys will be boys, and girls pick up the pieces. Simply flipping the script, or relying on the cliches about bad girls, is no good. It’s not until you try something like that that you realize how much even “literary” fiction relies on standard characterizations and narrative tropes. I once attended a lecture in which the speaker talked about the genius of Nabokov was evident in the fact that he made a rapist likable.

Trust me, that doesn’t take genius. We’ve been trained to find rapists likable from birth.

Anyway, when started writing Valya’s story, she absolutely insisted that she be given free rein to be her own bad self, which I sincerely hope makes people uncomfortable.

(By the way, if you want to pick up a free ARC of The Dreaming Land I, plus more books featuring Very Bad Boys and/or Girls, you can do so in the Villains and Minions Giveaway).

Valya is a Bad Girl in her own society, especially at the beginning of the story. In a culture that is trying, slowly and with lots of setbacks, to become less violent, Valya is a warrior princess who isn’t afraid to commit violence when she deems it necessary, as in this excerpt from Book I:

“Blades are made to be used,” I said noncommittally, and turned back to Ivan Marinovich.

“Yes—against the Hordes and people such as that,” said the other woman. Aksinya, I remembered, her name was Aksinya Yevpraksiyevna. Some of those Northern princesses had no taste at all when it came to naming.

“Of course,” I agreed.

“And I suppose you’ve had your fair share of opportunities to use them against those enemies, haven’t you?”

“I have,” I said. “Although it is not really fit talk for the feasting table.” Truth be told, I had only killed three raiders from the Hordes, although those three still loomed large in my memory. In these peaceful times, we strove to capture them alive and send them to the mines instead. They received mercy, and we received the benefit of their labor. I had taken more than two dozen prisoners, and the thought that they were now mining the ore for our swords was comforting.

“But using them against sister Zemnians is taking it too far, if you ask me,” Aksinya Yevpraksiyevna continued, her mouth drawing tighter and tighter and her eyes gaining a more and more triumphant glitter as she spoke. “Tell me, Valeriya Dariyevna: is it true? Did you really behead two of your own people last year?”

The rest of the table, and, I thought, the adjoining table as well, fell silent.

“My mother keeps no headswoman,” I said. “And yet someone must administer justice, and keep the peace. It was no different than killing raiders from the Hordes in battle.” Actually, that was a lie, but the self-righteous glares around me were annoying me, and I had no intention of letting them know how sick with horror I had been afterwards. Better that they should continue to fear me as a killer than pity me as a soft-hearted coward.

“Justice! In Zem’ we do not behead people in the name of justice, Valeriya Dariyevna! That kind of justice was ended in the reign of your great-great grandmother, if I remember aright. No one keeps a headswoman anymore, Valeriya Dariyevna, because there is no need!”

“It was necessary,” I said. “It was the best thing to be done with them.”

“Why? What could they have possibly done that required beheading, Valeriya Dariyevna?”

“Something best not discussed over supper,” I said. “And you do not know the whole story, Aksinya Yevpraksiyevna.”

“Oh, I think I do, Valeriya Dariyevna. Everyone knows you got a taste for violence after…well, and then those excursions against the Hordes,” she nodded at the scar on my arm, causing Ivan Marinovich to glance down at it too and blush yet again, “and so now, when there is nothing better for you to do, you must go bringing violence to your own people. Did you not write in last year to the Princess Council, urging us to mount a force and march East against the Hordes? Thank the gods that yours is not the only voice the Empress heeds. And then beheading two of your own people—not just Zemnians, but people of the steppe, even, well…”

“They were selling our children to the Hordes!” I shouted.

Here’s that link to the giveaway again, if that taste has whetted your appetite.

And Valya is also a Bad Girl by the standards of our society (and many parts of hers as well) in other ways. She sleeps with women. She sleeps with men betrothed to other women. She sets out to seduce a younger man, and engages in a relationship that has a strong element of D/s, with her as the D, with him.

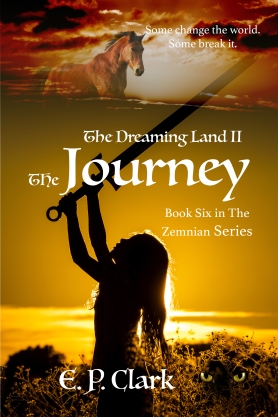

If your appetite is now even more whetted, you can pick up a copy of The Dreaming Land II, where a lot of the really racy action happens, plus many other books featuring Very Bad Girls, in the 9 1/2 weeks Giveaway.

And she also has a change of heart. Her big mission throughout the mini-series (which is very long, FYI, just mini in the context of the entire uber-series) is to catch the slave traders who are stealing and selling children. The first time she succeeds, as suggested by the excerpt above, she kills them. But the more she encounters them, the more compassion she feels for them, and the more she recognizes herself in them:

“But…” He looked away, and then looked back, frustration cutting grooves in his face. “How can you be so, so calm about it! You…you were the one who beheaded people for trading slaves? And now you’re going to just let them go! Not only that, you’re going to give them money!”

“The irony is not lost on me.”

He gave me a look of disgust.

“Very well, then: it makes me sick. It makes me sick to let Liza and her people go, and it makes me even sicker to give them money. If you had asked me a year ago, or even a month ago, what I would have done, I would have…I would have told you that like as not I’d kill them where they stood and leave them to rot, and call it justice. I…and I half-thought that was what I was going to do, right up until the moment I didn’t. But you see, when I…when I thought of doing it, it made me…it made me sick, and it made me even sicker to think of Mirochka ever finding out. I can’t let her have a killer for a mother.” I thought for a moment. “Or any more of a killer than I already am. And then…when she looked at me, when Liza looked at me, I knew…I knew that could have been me. She could have been me.”

“You would never do anything like that! You would never be anything like her!”

“No? I’ve killed people, Vanya! You’ve seen me do it!”

“Bad people!”

“And the people she was selling were bad people too! At least at the beginning.”

“They were children!”

“As if children can’t be evil. But you see…I understand why she did what she did, and I can’t say I wouldn’t have done the same, if I had been her. Because she’s right: what else could she or the people she thought she was helping do? It seemed like the best way out for them, and sometimes they were right. You see, Vanya, when I look at these slave traders, I no longer see the enemy. I see myself.”

“You’re…” His face worked. “You’re nothing like them!”

“Yes I am. Or at least parts of me are. So…I can hardly believe it, any more than you can, but I find myself compelled to be merciful to Liza and those like her. Not just because I think it’s the right thing to do and will make things better in the long run, although I do, but because I want to. I look at them and I feel…compassion. Recognition. Even when I hate them, when I want to hurt them, it’s because I hate that part of myself, the part of myself that would do anything, that is willing and able to hurt others in order to get what I want. So I have to do this, Vanya. Not just because it’s the best thing for our mission, but because I need to forgive that part of myself and let it go. Or rather, I need to be able to forgive that part of myself and let it go so that I’m not trapped by it, so that I can do what is best for us and all those we’re trying to help. I can’t be held down by the hatred I feel for people like Liza, people who represent everything I’m terrified of becoming. Anger…anger, rage, all that can give me strength, if I let it, if I channel it properly, but hate…you have to be careful with hate. You have to take it only in very small doses, like essence of poppy. A half a spoonful can help you get through things you wouldn’t be able to get through otherwise, but any more and it will kill you. So I’m letting go of all that, as best I can, and letting go of Liza and everything she stands for. I can’t let her get in the way of saving those who need to be saved, of saving Zem’ itself, maybe.”

I confess I did it on purpose. I tried to think of what readers would find most horrifying, and ask them to feel compassion for it. People, especially women, who steal children away from their families and sell them into slavery are probably really high up on the list of bad guys for much of modern American society. Too bad we keep doing it. And like Valya says, we probably won’t be able to stop doing it until we can find it in our hearts to forgive it.

Fascinating post, Elena! Your description of Valya reminded me a bit of Lisbeth Salander in Stieg Larsson’s Millennium Trilogy (“The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo,” etc.). I think she’s one of the best “bad” woman characters in modern literature — and VERY three-dimensional.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! I wasn’t thinking specifically of Lisbeth Salander when I wrote Valya, but I agree, she (Lisbeth) is a great bad girl heroine!

LikeLiked by 1 person